James Waller, Ph.D., Research Meteorologist

The El Niño phenomenon is signaled by warmer than normal sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the tropical East Pacific. The large-scale circulations associated with El Niño enhance wind shear (changing wind speed with height) in the tropical Atlantic. The enhanced wind shear disrupts tropical cyclone formation, generally associated with fewer tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Basin. The suppressing effects of El Niño are found to be strongest in the deep tropics (Kossin et al., 2010).

According to the NOAA Climate Prediction Center (CPC), El Niño conditions are likely to develop by mid-summer at the latest. Currently, conditions in the tropical Pacific clearly indicate that an El Niño is forming.

The unresolved questions are how strong this El Niño will be and whether the warmer waters in the tropical Pacific will be in the extreme East Pacific as with a textbook El Niño, or located more towards the Central Pacific. These questions are important because they influence where and how strong the disruptive wind shear will be over the Atlantic. These details could influence basin activity this year, particularly for those storms of the deep tropics and East Atlantic.

The 2004 season was a weak El Niño year with the warm waters located closer to the Central Pacific. The season produced nine hurricanes and five U.S. landfalls, four of which severely affected Florida in a very impactful season. The 1969 season was also a weak El Niño season, producing twelve hurricanes and two landfalls, one of which was Camille - the second strongest landfalling U.S. hurricane in recorded history.

TROPICAL ATLANTIC SSTs

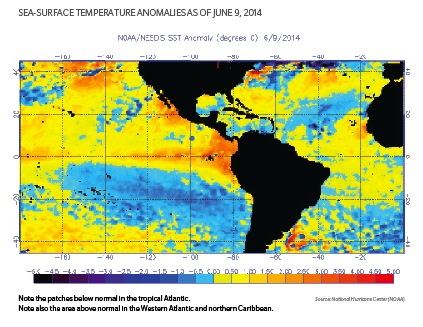

Seasonal outlook providers note the cooler than average SSTs in the tropical Atlantic as one factor for their quiet seasonal predictions. A closer look at SSTs in the Atlantic MDR indeed indicate moderately cool SSTs over a sizeable area.

However, on closer inspection, above normal SSTs are found in an area adjacent to the U.S. East coast and Florida (See figure below). The implications are that:

1. Tropical cyclone development may indeed be suppressed in the deep tropics and for African Cape Verde-type storms.

2. Disturbances adjacent to the U.S. mainland and northern Caribbean may find an environment with warmer SSTs and better enabling conditions for development of tropical storms. This applies both to disturbances generated in the area and also for Cape Verde-type disturbances that arrive from their Atlantic transit, even if they have not had a chance to develop.

3. If the El Niño-suppressing effects are weaker and shifted away from the southern United States and northern Caribbean, then a better-enabled environment for storm production is possible.

IMPLICATIONS

In light of the expected El Niño and cooler than average SSTs over the Atlantic MDR, some subtle but important factors warrant consideration:

1. The strength and placement of the El Niño remain uncertain and could displace the effects of disruptive wind shear.

2. The suppressive effects of El Niño are found to be strongest over the deep tropics (Kossin et al., 2010) and Cape Verde origin storms and less pronounced for Gulf-origin storms of higher latitude.

3. SSTs are somewhat cooler than normal over the East and Central Atlantic, but not for the waters adjacent to the eastern United States and northern Caribbean.

4. Disturbances originating in the West Atlantic or northern Caribbean may find an enabling environment in which to develop. The same argument applies for Cape Verde-type disturbances arriving in the West Atlantic (even if they had not experienced development during their Atlantic transit).

5. Landfalls are influenced by large-scale weather circulation at the time of occurrence, which by experience we know can be surprising to the world's best forecasters.