- Typhoon Nanmadol made landfall in the less-populated southern island of Kyushu, unlike Typhoons Jebi, Faxai and Hagibis, which first entered the east shore of Japan’s main island, Honshu.

- Nanmadol’s greatest impact was in Miyazaki Prefecture, where most of the fatalities and wind, flood and landslide damages occurred.

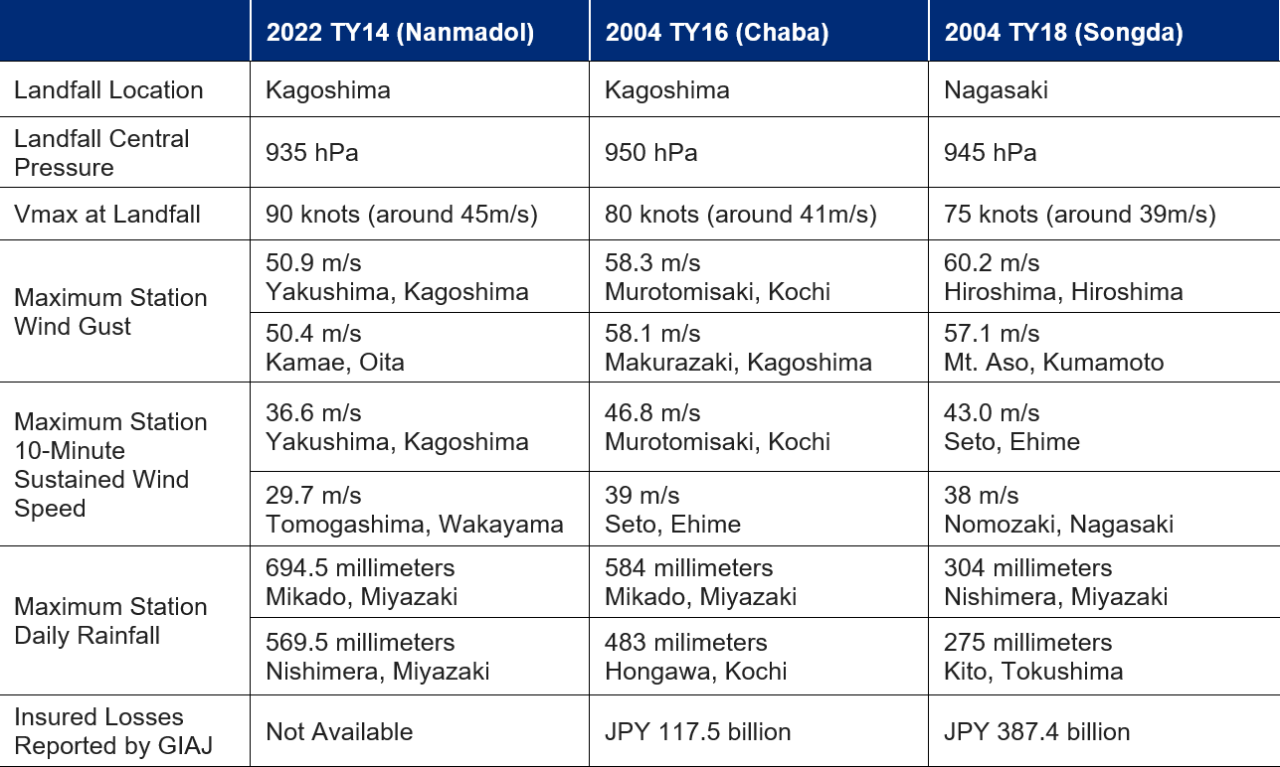

- Historically, Nanmadol is among the top-5 typhoons in terms of central pressure at landfall. However, its wind speeds were generally lower than those of 2 similar typhoons from 2004, Chaba and Songda.

- Nanmadol generated substantial wind, flood and landslide damage, but its storm surge was not severe.

This post-event report comprises the following sections:

- Physical Discussion of Meteorological Conditions

- Damage Impacts

- Large Insured Losses

- Comparison with Historical Events

Physical Discussion of Meteorological Conditions

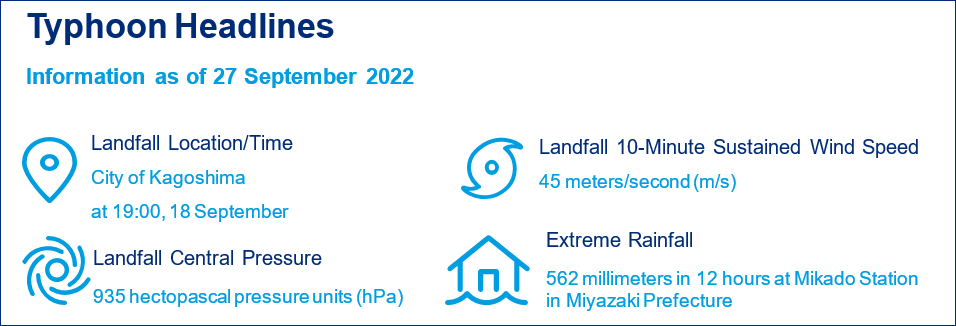

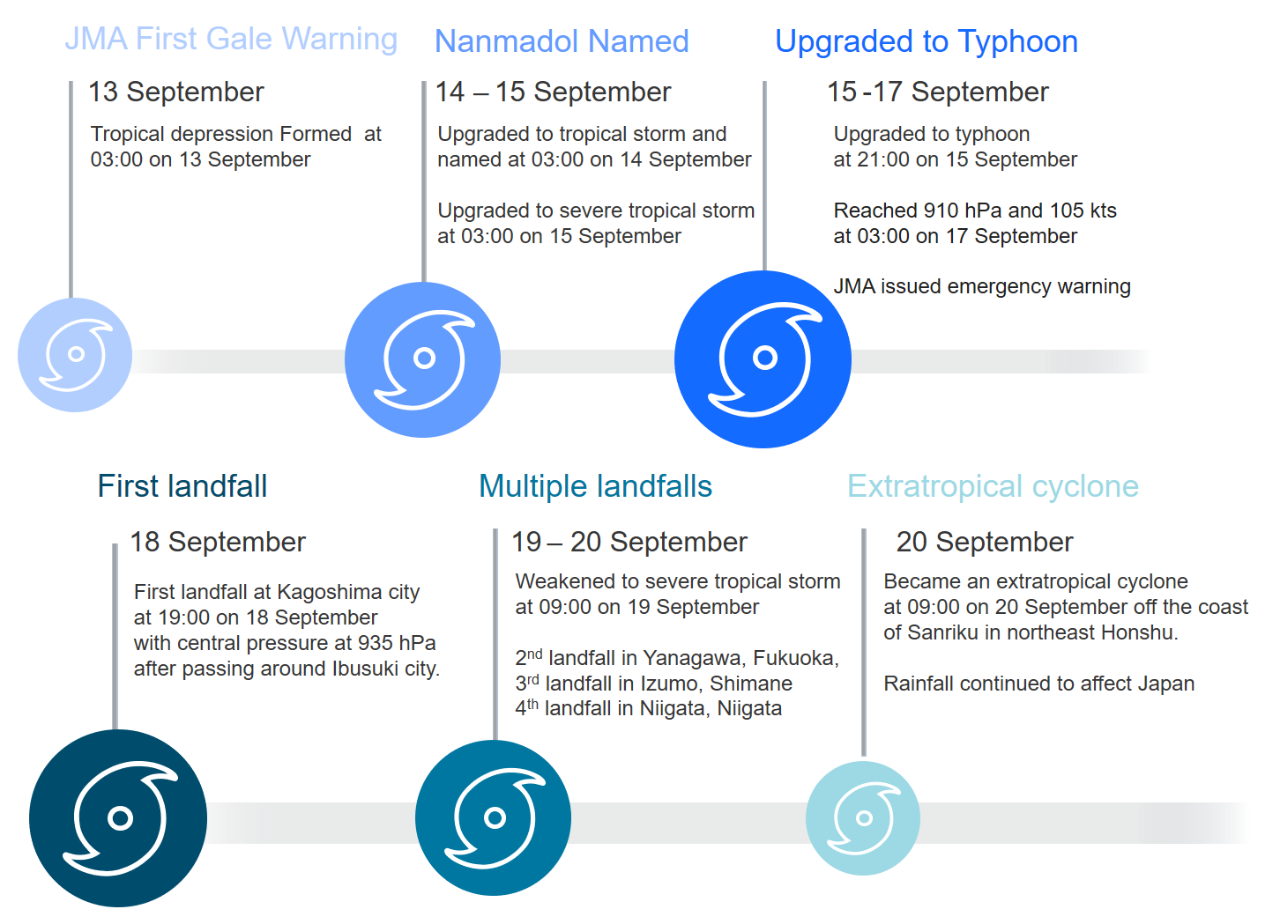

Figure 1: Key Dates

Nanmadol, the 14th named storm of 2022 in the Western North Pacific, formed on Tuesday, 13 September southwest of Iwo Jima, over the open waters of the Philippine Sea. In the days following its formation, Nanmadol tracked slowly northwest, with a recorded central pressure of 910 hPa, the lowest so far this season. Nanmadol passed by Ibusuki, Kagoshima Prefecture, around 17:30 local time on Sunday, 18 September.

Nanmadol’s center made first landfall near the city of Kagoshima in Kagoshima Prefecture, around 19:00 local time on Sunday, 18 September. At landfall, Nanmadol had a 10-minute sustained wind speed of 45 m/s and a central pressure of 935 hPa, according to the JMA. The center of the system tracked over the prefectures of Kagoshima, Kumamoto and Saga, and Fukuoka of Kyushu during Sunday. A strong frontal system ahead of a mid-latitude trough approached from the northwest overnight and into Monday, 19 September, resulting in Nanmadol taking a turn to the northeast across northern Kyushu toward southwestern Honshu.

Interactions with the mountainous terrain of Kyushu gradually weakened Nanmadol as it progressed farther inland, and more rapid weakening occurred when it turned northeast into southwestern Honshu. The system brought typhoon-force winds and heavy rainfall to Kyushu and parts of the neighboring island, Shikoku. Nanmadol attenuated to a severe tropical storm at 21:00 on Monday, 19 September, with its center over northeast Fukuoka Prefecture on Kyushu. Later, southwestern Honshu and central Japan were impacted. Nanmadol became an extratropical cyclone at 09:00 on Tuesday, 20 September off the coast of Sanriku in northeast Honshu.

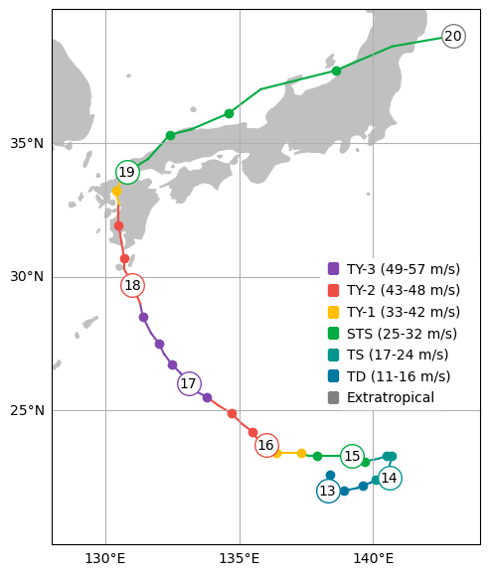

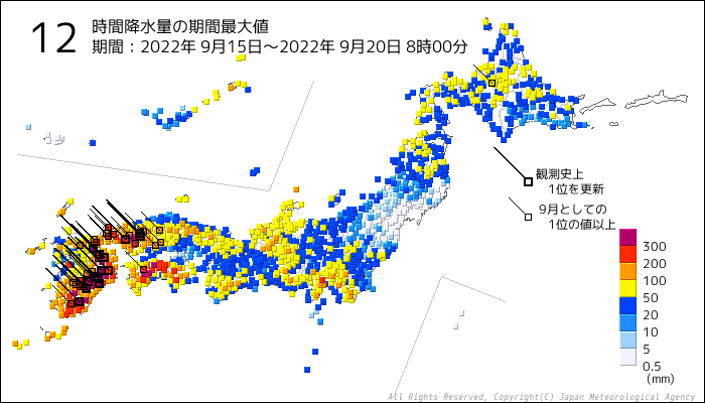

Along its path, strong wind and high volumes of precipitation were recorded, resulting in widespread wind and flood damage. Figures 2 and 3 below show its track and intensity, along with the precipitation distribution across Japan.

Figure 2: Storm Track with Wind Intensity from 13 September to 20 September

Sources: JMA and Guy Carpenter

Figure 3: Observational Maximum 12-Hour Precipitation as of 08:00 on 20 September, from the period 15 September to 20 September

Source: JMA

Damage Impacts

As of Monday, 26 September, Japan’s Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA) reported 4 fatalities, 3 in Miyazaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu, and 1 in Hiroshima Prefecture on the main island of Honshu. The FDMA also reported 147 injuries, 19 of them severe, 365 affected buildings, of which 6 were totally damaged, 10 were half-damaged and 349 were partially damaged. In addition, it found 1,181 flooded buildings, including 693 with more than 1 foot of water.

On the same day, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) published its survey, noting that landslides caused 3 buildings to be totally damaged and 11 buildings to be partially damaged. The MLIT examined 174 houses with inundation, but they did not seem to be damaged. They found 9 public-housing buildings in Fukuoka and Oita Prefecture with roof damage, resulting in water entering into the properties. An exterior wall of a warehouse in Miyazaki Prefecture also was found damaged. On the island of Tanegashima in Kagoshima Prefecture, a wall was damaged at the space center owned by the Japan Aerospace and Exploration Agency, and the impact to the rocket assembly had to be assessed. At the construction site of an apartment building in the center of the city of Kagoshima, high winds bent a crane, and the area had to be evacuated.

Mountainous areas suffered mudslides, which—together with fallen trees—led to many road closures. In Miyazaki Prefecture, such conditions resulted in a collapsed bridge. Many public parks in Kyushu had downed trees, broken fences and damaged lighting, also leading to closures. Part of the Hikone Castle structure, a national treasure in Shiga Prefecture, suffered damage, and in the town of Kunitomi, fields and greenhouses were submerged due to heavy rain. Some farmers had just planted seedlings and now may have to replant.

In Saga Prefecture, the MLIT found that 2 sewage treatment plants had stopped operations due to power outage, but subsequently resumed normal service. One plant in Miyazaki Prefecture was flooded, and another was partially flooded and lost power. These two plants temporarily switched to alternative service.

The MLIT also published 20 completed surveys and 12 ongoing investigations of damage to marine assets. It observed numerous barges and piers that had been damaged, drifted away or sunk. Along the beaches, ports and harbors of Kyushu, boats had flooded, capsized, sunk and washed ashore.

Since Nanmadol arrived during a 3-day holiday weekend (Saturday, 17 September-Monday, 19 September) with several days of warning, travel disruptions were moderated, but high-speed bullet-train services were suspended between economic hubs in the affected areas. No bullet trains ran in Kyushu, or between Hiroshima and Fukuoka, on Monday, 19 September, and bullet-train services were interrupted between Osaka and Nagoya on Monday night. The JR Hokuriku line suspended a total of 90 limited express and local trains on 19 September, and 35 limited express trains were suspended until noon the next day. Many harbor services also were canceled because of high waves. The MLIT reported interruptions of 11 ferry routes earlier, although over half of them soon resumed normal operations. From Saturday, 17 September to Tuesday, 20 September, there were 2,555 flight cancellations, including closures at international airports serving Tokyo, Osaka and Fukuoka.

Supply-chain disruptions also were notable. The 907 TEU (20-foot equivalent) SITC Nagoya, operated by SITC Container Lines, departed the port of Dayaowan, Dalian, but diverted course to South Korea’s Mokpo port on 18 September, thus delaying its arrival in Hakata by 3 days (from 18 September to 21 September). The 338 TEU Ji Peng, operated by Success Shipping, started at the port of Weifang, Shandong, dropped anchor at Penglai, Shandong, and delayed its arrival at Hakata by 2 days (from 20 September to 22 September). The 604 TEU Acacia Ares, operated by Starocean Marine, departed Shanghai on 18 September, but took shelter in Zhapu Port, Zhejiang, delaying its arrival at Moji by 1 day. FourKites, a supply-chain internet platform that tracks shipping, reported a 38% drop in imports to Japan from 17 September to 21 September.

According to Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, power outages were widespread, with 135,000 households having lost electricity. This included 120,000 households served by the Kyushu Electric Power Company. The prefectures of Chiba, Saitama, and Yamanashi also were impacted, and cellphone service was interrupted on Kyushu, with disruptions reported in central Japan as well. In some areas, mobile base stations had to be brought into service.

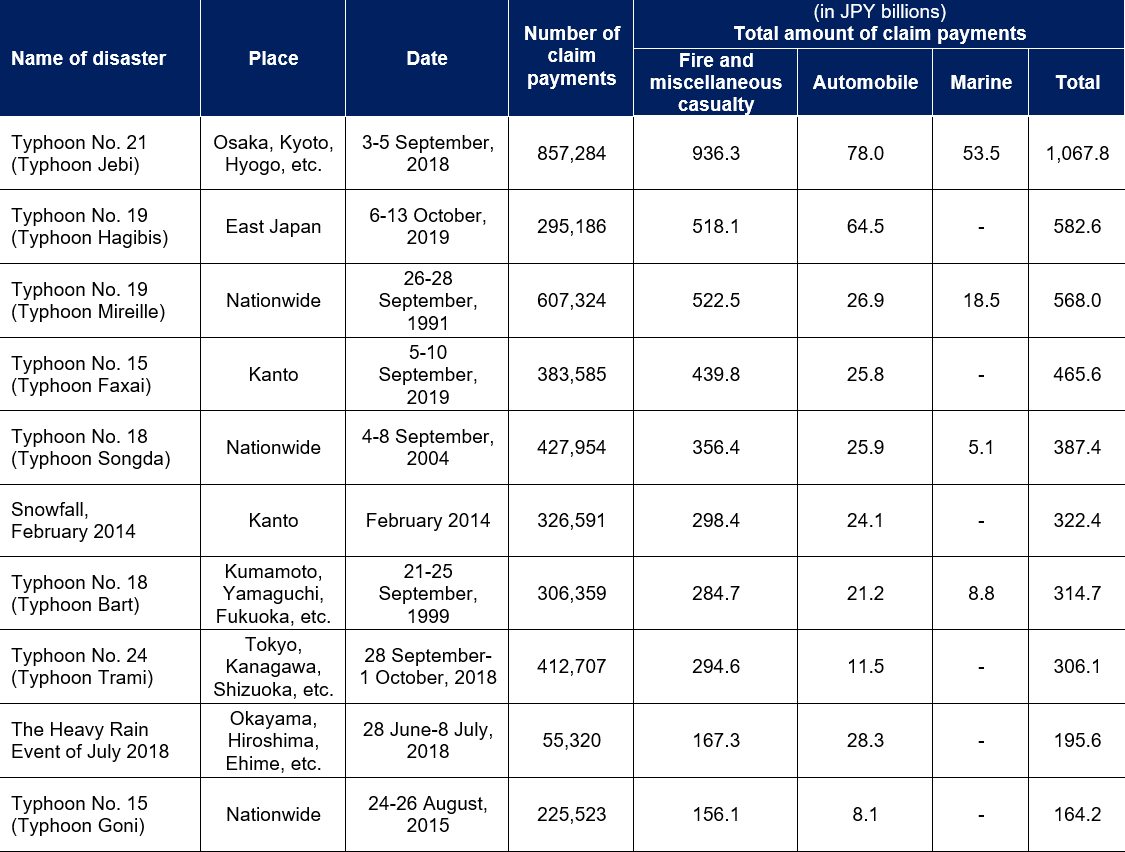

Large Insured Losses

The table below from the General Insurance Association of Japan presents claims paid, as of March 2022, from Japan’s top-10 historical typhoon and windstorm events across all domestic and foreign insurers. These amounts are based in part on estimates, exclude payments from mutuals, and have not been trended to present value.

Table 1: Top 10 Historical Events Ranked by Total Insurers’ Paid Claims

Source: GIAJ

Comparison with Historical Events

Nanmadol’s central pressure of 935 hPa at landfall is among the top-5 lowest since 1951, trailing behind Typhoons Nancy (1961, 925 hPa), Vera (1959, 929 hPa) and Yancy (1993, 930 hPa), but equal to Typhoon Ruth (1951).

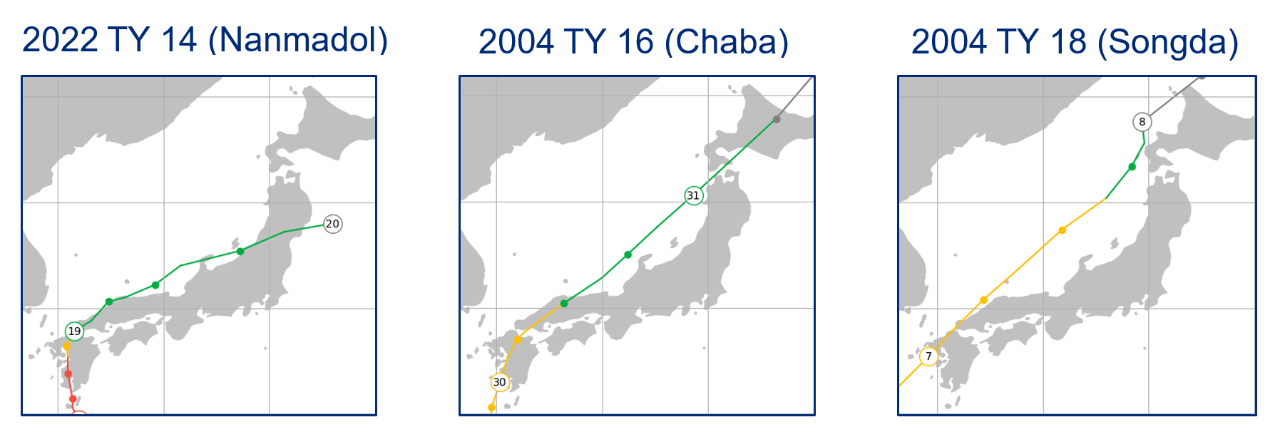

Nanmadol’s track differed notably from the 2018-19 Typhoons Jebi, Trami, Faxai and Hagibis, which entered the eastern shore of the main island, Honshu. In this regard, it was similar to Typhoons Chaba and Songda of 2004, which made landfall on the southern island of Kyushu, then entered the southwestern prefectures of Honshu, before turning northeast through the Sea of Japan, across Honshu, and out to the Pacific Ocean.

Figure 4: Storm Track and Intensity of Nanmadol, Chaba and Songda

Sources: JMA and Guy Carpenter

Table 2: Highlights of Similar Events

Sources: JMA and GIAJ

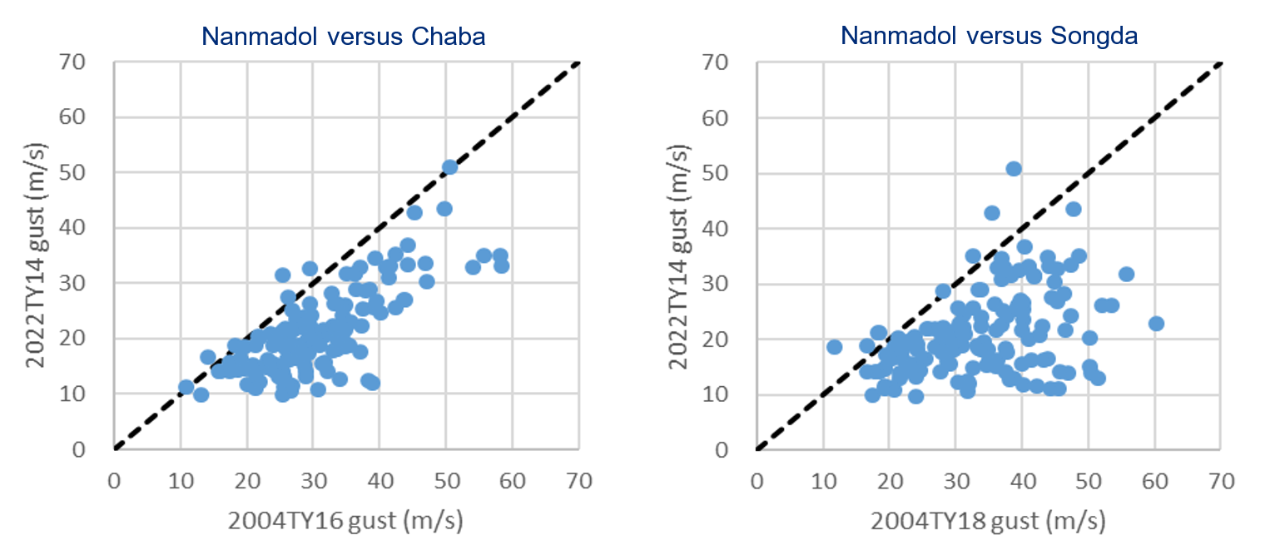

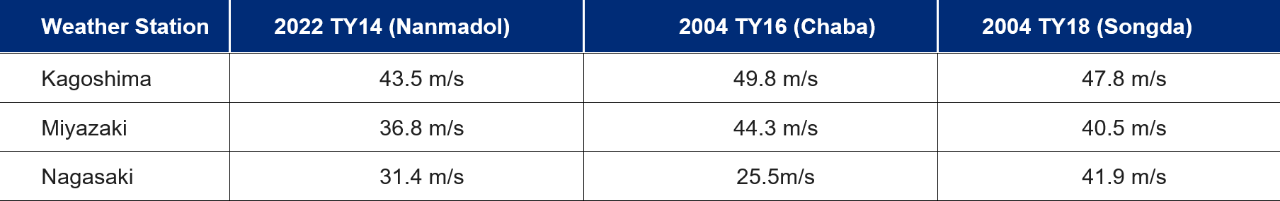

Peak Gust Wind-Speed Comparison

Even though Nanmadol’s landfall central pressure was among the lowest in historical typhoons affecting Japan, we found that its gust wind speeds often were lower than those of Chaba or Songda.

Figure 5: Station Gust-Speed Comparisons of Chaba and Songda with Nanmadol (as of 08:00, 20 September)

Sources: JMA and Guy Carpenter

Table 3: Comparing Peak Gusts at Select Weather Stations

Sources: JMA and Guy Carpenter

Estimating impact of a catastrophe is a multi-dimensional challenge. In today’s economic environment, there is the added concern of inflation. Although this problem faces Japan, its current inflationary trend is much lower than that of the US or most European countries. Nanmadol’s severe wind and heavier rainfall impacted Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefecture, which are not densely populated in comparison to the main areas affected by the 2018-2019 typhoons. Its track was similar to Chaba and Songda of 2004, but its wind speeds often were lower, and it was not associated with notable storm surges like Songda. Furthermore, Japan had carried out multiple building-code upgrades after several disasters, so current building stock should be more resilient to wind than the one in 2004. Overall, Nanmadol’s hazard parameters were within expected ranges, and there was substantial warning ahead of time. These factors together are helpful to mitigate both loss of life and property damage.

Sources: Japan Meteorological Agency, General Insurance Association of Japan, Fire and Disaster Management Agency, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, Associated Press, Japan Times, Nikkei Business Publications, Hokkoku Shimbun, Container News, Twitter, NASA WorldView.