Climate change and extreme weather are increasingly important for multiple stakeholders, including regulators, rating agencies, investors and risk managers. This briefing examines how climate change affects physical risks posed to insurers with Mainland China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan exposure and the evolution of regulation associated with this risk.

Introduction

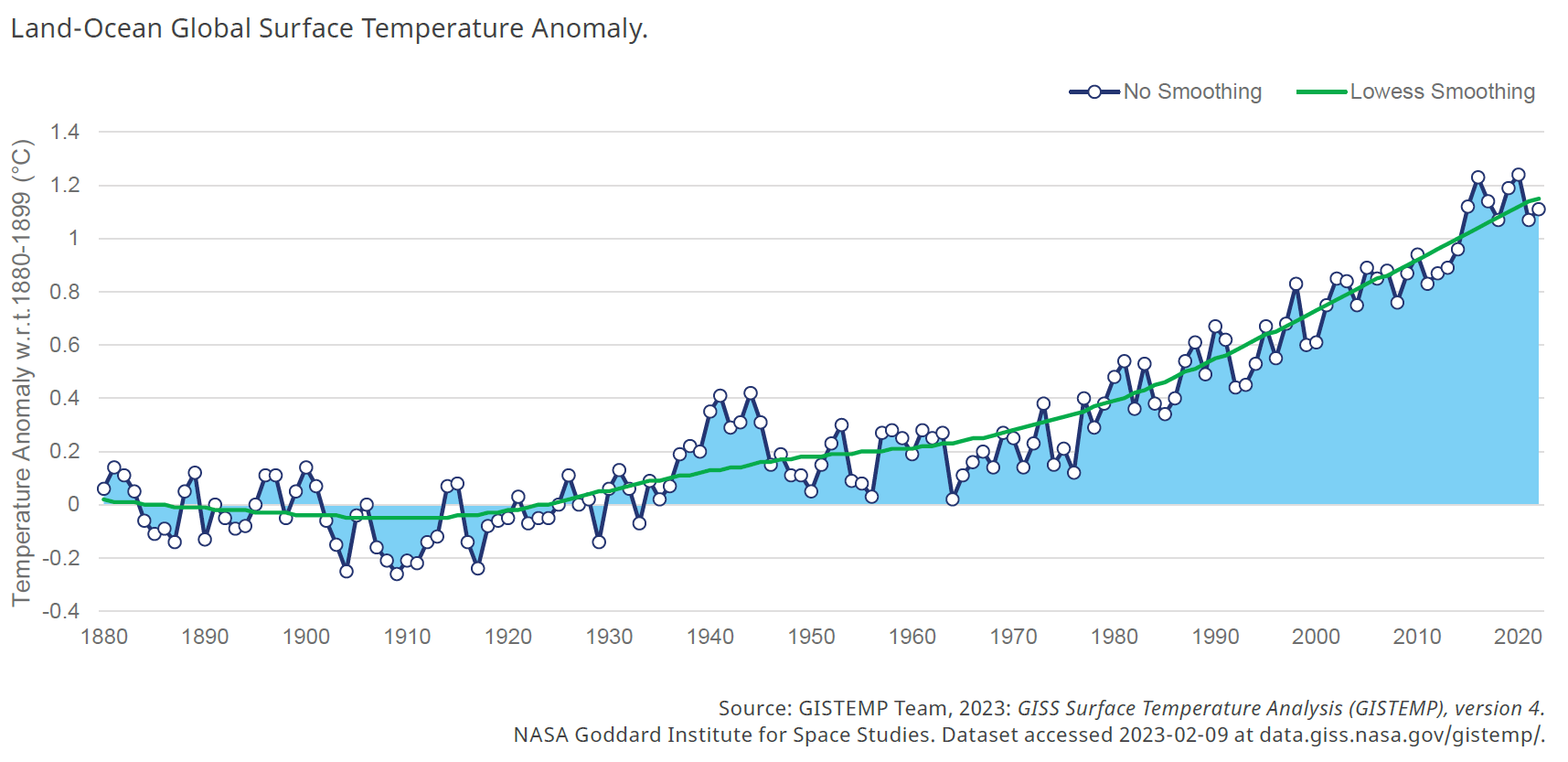

There is increasing pressure on insurers to understand climate change’s impacts on damaging weather. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) reported that 2022 was the fifth-warmest year on record, with the average surface temperature 1.11°C warmer than during pre-industrial times (see figure below).

The global temperature is projected to increase further and will reach 1.5°C around 2030 without a radical reduction in emissions. These seemingly small increases in temperature can have a large non-linear impact on a wide range of perils, including drought, flood and tropical cyclone. If there are no reductions in emissions in the medium term, 3°C of warming is likely before the end of the century, which would bring more severe consequences.

Recent events such as the flooding associated with Typhoon Hagibis (2019) and extreme precipitation episodes in Mainland China (2020) have been partially attributed to climate change. (Re)insurers can avoid unexpected losses—and help achieve long-term growth and profitability—by quantifying their exposure to the physical risk of climate change. (See figure below. Click the image to see larger version of the graph).

Evolving Risk Landscape

The frequency and severity of natural catastrophes are expected to increase due to climate change. The subsequent impact on insured loss is highly dependent on the peril and region of interest, and is described in the section Climate Change Impact by Peril.

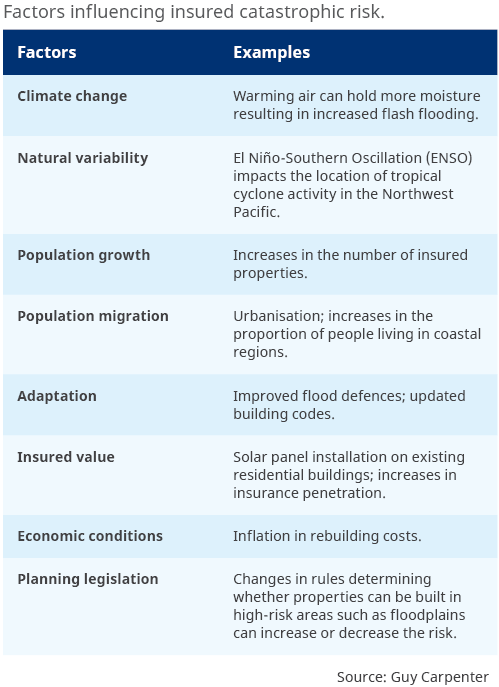

Climate change is not the only factor influencing how the financial catastrophic risk to re(insurers) changes from year to year. Climate change generally changes the risk gradually over time, although the financial impact may only be realised when a significant event occurs. In contrast, other factors can lead to more abrupt changes in risk, for example, inflation in rebuilding costs or the implementation of flood defences. These other factors will often have a larger impact than climate change, and we compare examples of them with climate change in the table below.

Managing Climate Change Physical Risk In East Asia

Regulation

Climate change presents 2 key forms of financial risk: those associated with a transition to a lower-carbon economy, and those related to the physical impacts of climate change. The physical impacts can be assessed and reported as either chronic or acute. Chronic physical risks are gradual changes in weather patterns, such as rising sea levels, droughts and extreme temperatures. Acute physical risks are sudden and severe events that can cause significant damage to property and infrastructure, such as hurricanes, floods, wildfires and storms. Regulators have started to ask companies to assess their exposure to both types of risk.

Mandatory climate change financial reporting, often aligned with the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), has come into effect in several jurisdictions. Given the uncertainties of these risks, responses are expected to be proportionate to the size, nature and complexity of the business.

In the East Asia region, supervisors are engaging with the (re)insurance industry to build capacity and understanding of climate risks and their impact on financial stability. Several countries have announced mandatory disclosures for listed companies, with most supervisors issuing guidelines on the management of climate risks.

In Hong Kong, the Green and Sustainable Finance Cross-Agency Steering Group (CASG) was established in May 2020 and encompasses a number of financial authorities (including the Insurance Authority). CASG’s Strategic Plan covers 6 key focus areas and includes mandating TCFD-aligned disclosures across relevant sectors no later than 2025 and supporting the development of International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) global sustainability reporting standards.

Similarly in Japan, revisions to the Corporate Governance Code encourage companies to develop and disclose initiatives and policies on sustainability as well as enhance the quality and quantity of climate-related disclosures based on TCFD recommendations, particularly for Prime Market listed companies.

Voluntary guidelines have been widely published across East Asia. The FSS in South Korea has introduced a guideline on the management of climate risks in the financial sector through a dedicated climate risk forum, and Japan’s FSA published Supervisory Guidance on Climate-related Risk Management and Client Engagement.

Taiwan’s FSC Guidelines on Climate-related Financial Disclosures of Insurance Companies require insurance companies to establish appropriate mechanisms for climate-related risk management and opportunities based on the scale and nature of their business activities.

Mainland China’s CBIRC has also launched its Green Finance Guidelines for banks and insurance companies to promote green finance, improve the level of sustainability, due diligence and risk management, encourage disclosures, and assist in pollution prevention and control.

These guidelines are highlighted in the table below.

Scenario analysis and stress testing have emerged as key forward-looking tools to assess the potential impact of climate risks. South Korea has announced it is considering industry-wide climate stress testing. In August 2022, Japan’s FSA together with the Bank of Japan published the results of a pilot scenario analysis that focused on physical risks (acute risks by typhoons and floods) related to underwriting business using three Network for Greening the Financial System scenarios (Net Zero 2050, Delayed Transition and Current Policies).

The results suggested that climate change may increase claims payments (through the intensification of tropical cyclones and increase in rainfall and river flow). However, the results should not be interpreted as a conclusive evaluation of the effects of climate risks. Going forward, the FSA will promote conducting climate scenario assessments using the same risk model (developed by the General Insurance Rating Organization of Japan). They may also ask insurance companies to conduct stochastic analysis that considers the probability of occurrence of various scenarios that incorporate the impact of future climate change.

Overall, although the regulation in the region remains at an early stage, there is a growing interest from supervisors in bolstering capabilities and understanding of climate change financial risk management across the industry.

Climate Change Impact by Peril

We evaluate the impact of climate change on a peril based on observations, climate models and our understanding of the physical drivers. In cases where we have a consistent view—a long observational record, high-resolution climate model output and a good understanding of the physical drivers—then we will have high confidence in our assessment. Conversely, there are many reasons why we would have lower confidence, for example, if an observational record is short or unreliable, or if there is disagreement between different climate models. Here we summarise the climate change impact on tropical cyclones (TCs) and floods. Note that climate change does have a significant impact on a wide range of other perils, including wildfire, hail, drought and heat stress, but these typically have lower insured losses associated with them in East Asia.

Climate Change Impacts on Tropical Cyclone

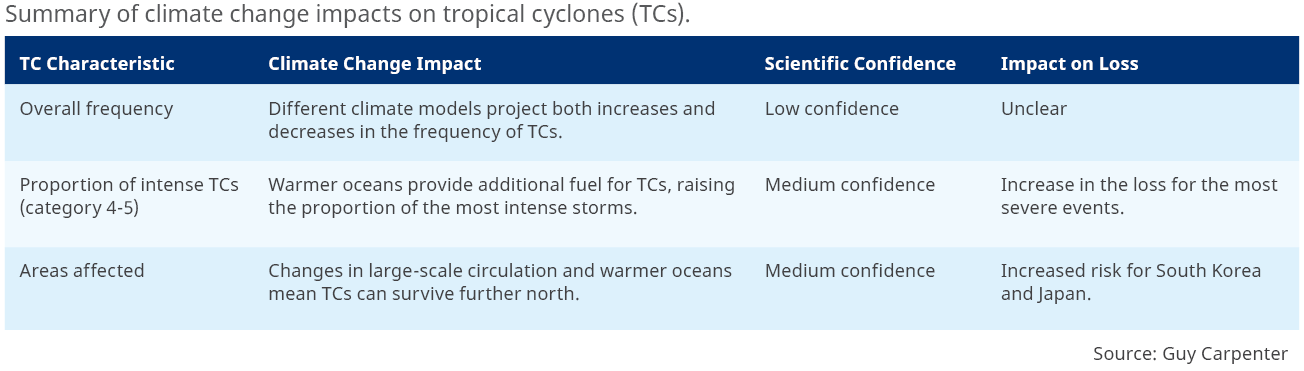

Climate change affects the frequency, severity and location of TCs in the Northwest Pacific basin, as outlined in the table below. The impacts are wide-ranging, as the energy source of TCs (the ocean), the winds that inhibit their growth (wind shear) and the large-scale circulation pattern that steers them are all affected. There are also implications for the precipitation and coastal flooding associated with TCs, included in the table Summary of climate change impacts on flood.

Climate Change Impacts on Flooding

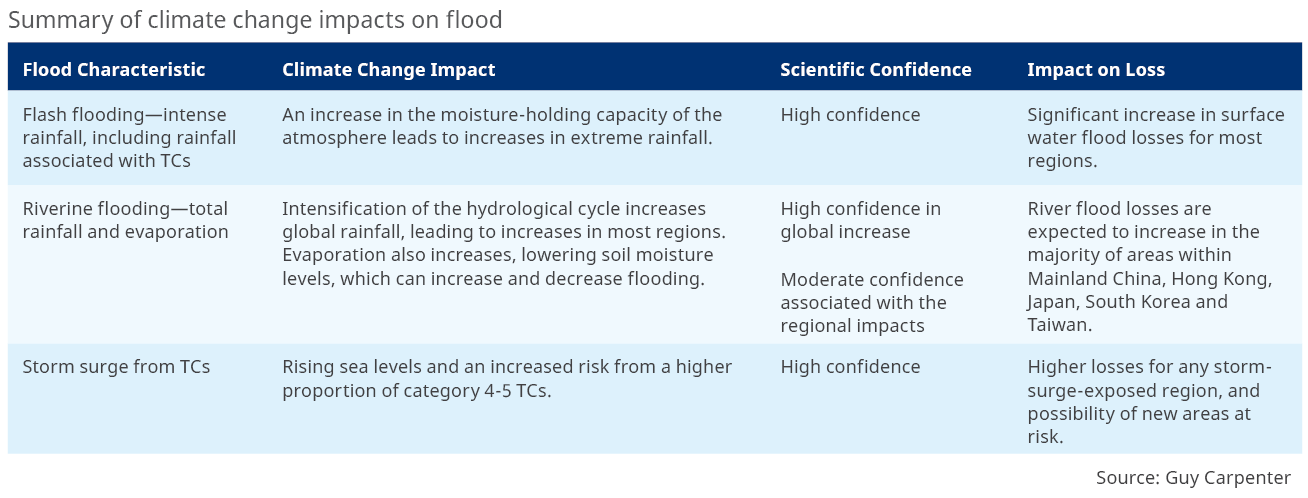

The impact of climate change on floods is complex. Intense rainfall has a relatively direct link to surface water flooding, and therefore the climate change impact is generally well understood. In contrast, the response of river flooding to precipitation is dependent on a large number of factors, including soil moisture, temperature, snowmelt and catchment characteristics, and therefore changes are harder to predict and highly regional.

Quantifying your Climate Change Physical Risk

There are a growing number of reasons for quantifying your climate change risk:

- Responding to regulatory requests.

- Representation of risk to third parties—for example, credit rating agencies, investors or reinsurers.

- Making a TCFD-aligned climate disclosure.

- Incorporating climate change into risk management, pricing and capital decisions.

The type of risk assessment to carry out will be dependent on the use case. Important questions to consider before making any climate change assessment include the following:

- Is a qualitative or quantitative assessment required?

- What scenarios are of interest? This could be a specific emissions pathway and time horizon, for example SSP5-8.5 in 2050, or instead a global warming level scenario, for example 1.5°C.

- Do you require an assessment of whether existing climate change is adequately represented in your current view of risk?

- What form of data is required to embed the climate change assessment in your existing decision-making processes?

Guy Carpenter is helping our clients address these questions and quantify their climate change physical risk through a variety of methods. For the quantification of the risk, Guy Carpenter has developed proprietary tools ranging from underwriting and accumulation layers to adjustments to third-party catastrophe models and in-house probabilistic models developed for climate change. Furthermore, we have a broad overview of market practices that can help clients benchmark their own activities.

We have model adjustments that provide a fully probabilistic climate change assessment for inland floods. In addition, for Japan, we also have a tropical cyclone model adjustment.

Conclusions

An improved scientific understanding of how perils are changing and an increasing number of regulators exploring climate-related disclosures means quantifying your climate change risk has never been more important. Doing so may also help avoid unexpected loss from evolving tropical cyclones and flood risk. It is also important to be aware that climate change may not be the most significant driver of changes in loss for your portfolio. Other factors, such as natural variability and inflation, should be properly considered to inform risk management, pricing and capital decisions.